Do not settle for the first draft. The best stories evolve from the search for the right angle and fearless rewriting. The article, Swapping Fool’s Gold for Real Gold , in the Spring 2004 issue of Idea File, Volume 14, issue 3, discussed getting writers to find the most interesting aspect of the story they are covering – known as the nugget. It’s the nugget that makes the story about the same topic unique from year to year.

List of stock questions for writers after

they have presented their first draft

Rewriting is the secret to good writing. Embrace it, and you will produce final drafts of interest. Reject it, and you will limit your writing to mediocrity.

When rewriting, read the story aloud so you can hear the tone and inflection of your work. Awkward working usually screams at you during this recital. It’s also good to have a friend read your story. Don’t hesitate to obtain objective opinions.

Before you begin to write, read over your interview notes and gather related terms and important information. Listing and clustering start the juices flowing; they put you in the writing mode.

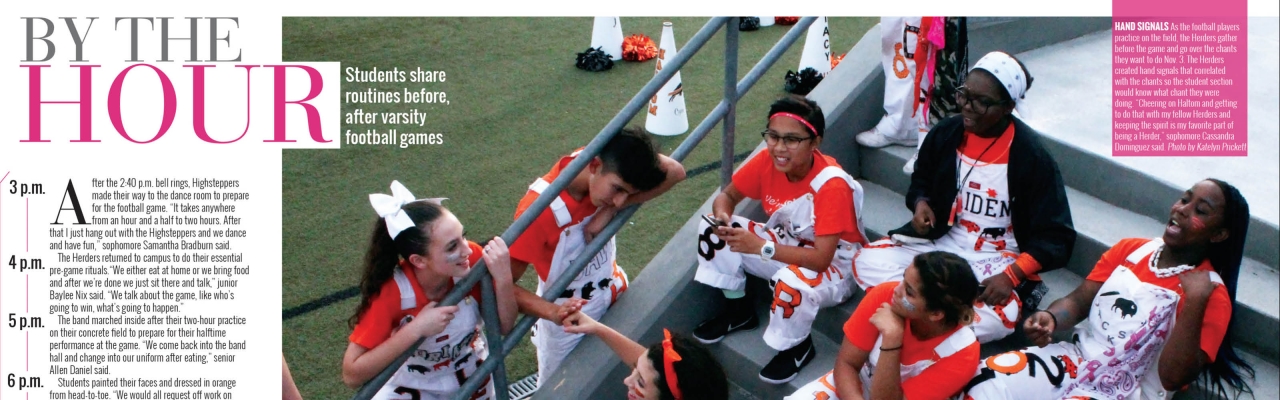

The old saying goes, “A picture is worth a thousand words.” However, without a caption, readers may get a thousand different messages from a picture-and all of those messages may be wrong.

Story leads work much like ice cream toppings. They draw attention to the subject, making it more attractive, imparting a distinct “flavor” or “personality.”

Leads can inspire. They can question. They can shock, tickle, tease or entertain. But what is their ultimate purpose? Working together with headlines, designs and photographs, leads invite readers to come inside, kick off their shoes and stay for awhile. Good leads should not just grab attention; they should also harmonize with the tone or attitude of the copy. Even the cleverest lead, however, cannot salvage a poorly written story. A punchy lead followed by a boring story is a letdown. Instead, that same lead should pull the reader into a fabulous story that deserves to be read. All of the elements need to function together to make a meaningful presentation.

Talking with students about the 5 Ws and 1 H used to mean that the news lead most certainly was the topic at hand. No longer. Talking about the who, what, when, where, why and how could also mean you’re discussing the writing of in-depth captions for your yearbook.

Yearbooks are made up of 16-page signatures, always beginning with a right-hand page and ending with a left-hand page. In the printing process, a signature is a large sheet of paper on which eight pages (a flat) are printed on each side. After both sides have been printed, the sheet is folded and cut so the pages are in book form.

I was about to give up when I remembered meeting Samuel Beckett at the NSPA convention last year in Seattle. I heard Beckett say that he had actually been a journalism teacher for several years and was presenting a session at the convention on how teaching yearbook had sparked his imagination for the tragicomedy, “Waiting for Godot.” In his session, he asked us to read selected scenes from the play to see the close connection. In fact, he said, although most people think he is writing about the angst of the 20th century, many of the scenes in the play are really about his frustration as a yearbook teacher trying to improve the academics section.

Each story happens in context.

Consider Gone With the Wind. The story, read and reread because of Scarlett’s passion for Ashley, also shows most readers as much as they care to know about the Civil War. The story takes shape in context.

The same principle applies to a yearbook story. Showing one student’s struggle in context will give readers information about the rest of the school.